It’s been decades since Michael Leslie has taken to the stage but the legendary Aboriginal dancer and choreographer is about to perform in his new work, 3.3. The piece will be presented by Ochre Dance Contemporary Dance Company alongside Beyond, by another Australian dance legend, Chrissie Parrott.

Why is 3.3 so close Michael Leslie’s heart? Nina Levy caught up with him to find out.

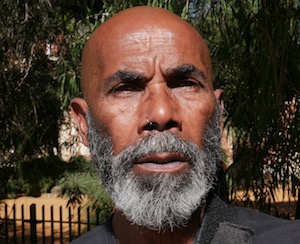

Talking to dancer and choreographer Michael Leslie about the upcoming season of his work 3.3, the first thing that strikes me is that this man is all about movement. It’s another (globally warmed) balmy May day and we’re sitting at a picnic table at the edge of the Subiaco Arts Centre’s lush gardens… at least Ochre Contemporary Dance Company artistic director Mark Howett and I are sitting. Leslie occasionally sits, but mostly he’s on his feet. It’s as though some thoughts and ideas are too vital to be discussed in a sedentary manner.

It’s not difficult to understand why Leslie is speaking with such passion. The title 3.3 is a reference to the fact that Aboriginal people represent 3.3% of the population of Australia, but more than 28% of its prison population. A Gamilaraay man, Leslie made 3.3 in 2017, as part of his master’s degree. The work focuses on a successful young Indigenous dancer (played by Noongar dancer Ian Wilkes), who has been arrested and thrown into a holding cell, persecuted on account of his skin colour and torn between two cultures. Blurring the line between fiction and reality, Leslie plays himself, the young dancer’s mentor, who deliberately gets himself arrested so that he can speak to the boy and encourage him to stay on the right track to succeed in the “white fella world”.

While the scene in the cell isn’t autobiographical, Leslie’s own story also involves navigating two different worlds as a young dancer. Born in north-west New South Wales, times were tough growing up, he says, subject to the racist government policies of the era. “Dance would have been the furtherest thing from my mind,” he recalls, but by chance, a television advertisement, featuring dancers, ignited his passion for the artform, at age 19. “I was hooked,” he remembers. “Taking the initiative, I commenced dance classes at the Bodenwieser Dance Centre on Broadway in Chippendale, Sydney, a school founded by Mrs Margaret Chapple, a pioneer of Australian Contemporary Dance.”

At Bodenweiser Dance Centre Leslie met Carole Johnston, an African-American dancer who founded the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association (NAISDA). One of five founding students at NAISDA, Leslie became part of a growing Aboriginal dance scene, performing with the newly formed Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre (AIDT) around Australia and internationally through the 1970s. In 1980 Leslie won a Churchill Fellowship, which enabled him to train at the famed Alvin Ailey American Dance Centre in New York.

Leslie returned to Australia seven years later. A co-founder of both Black Swan State Theatre Company and Broome-based dance theatre company Marrugeku, he also began to work extensively with young Aboriginal people, establishing the Aboriginal Centre for Performing Arts at WAAPA in 1996 and the Michael Leslie Pilbara Performing Arts program in 2006. He has received numerous awards and accolades for his work as an artist, educator and mentor.

“There was a law called linguicide, where it was forbidden for my people to speak their language and if they did they’d be thrown in gaol. That added to the demise of people speaking language. So when I did my master’s, I looked at creating 100 dance steps from the Gamilaraay language.”

Now 60, Leslie speaks with great anxiety about the future of young Aboriginal people, and one of his primary areas of concern is racial discrimination within the judicial system. An important part of 3.3, therefore, is highlighting the horrific miscarriages of justice that have been and continue to be inflicted on Aboriginal people since white invasion. As Leslie notes, the breadth of these is “mind-boggling” and so, for practicality, he has chosen to focus on massacres and violent incidents that have affected his people, the Gamilaraay. The first of these is the infamous Myall Creek massacre in in 1838. “The fact that [the settlers] didn’t shoot [the Aboriginal people], that they killed them up-close with swords? That’s hatred,” comments Leslie. “Then the second massacre was the Waterloo Creek massacre,” he continues, “when [white people] killed 300 of my people, on 26 January 1938 – that’s why a lot of black people don’t like Australia Day – and all [the perpetrators] got was a slap on the wrist for killing 300 people. Then in 1982 there was the murder of Ronald “Cheeky” McIntosh in Moree, and they shot Stephanie Duke, Warren Tighe, Michael Foote. When they pronounced Cheeky dead, my people came riding across the bridge and you know who’s waiting for them there? The Tactical Response Group. They’ve got sirens going, they’re holding hand guns, holding shot guns, mustering my people back to the fucking mission. This is 1982!

“So the story here is, where is the justice? There’s no justice for my people. What about Elijah [Doughty]? What about Miss Dhu? You tell us we’re citizens, we need to take responsibility. Well you need to wear that too. What they did to Miss Dhu was terribly, terribly wrong. And all they got was…” Leslie mimes a slap on the wrist. “And that’s what this piece is all about. It’s speaking for my people.”

But the work is about more than simply making people aware of these acts of murder and subsequent lack of justice, adds Howett. “It’s also about healing. Even though we ask hard questions, we’re trying to open up a topic enough so that people can discuss it and the can recover from it. There’s a chance for healing by showing the hardest part of one’s life.”

Part of that healing is about reclaiming language through movement. “There was a law called linguicide, where it was forbidden for my people to speak their language and if they did they’d be thrown in gaol,” says Leslie. “That added to the demise of people speaking language. So when I did my master’s, I looked at creating 100 dance steps from the Gamilaraay language. This was not only an artistic reclamation of language but a political act against linguicide.”

Those 100 dance steps, based on the rhythms and meanings of words from Gamilaraay language, form the basis of the choreography for 3.3. “I did a reclamation of my language, of my culture, to create what I’ve created in the cell there,” explains Leslie. “So every word that I chose, there had to be something where I could create a step. Like the word “Muti”, which means lightning, that’s a tour (a jump that turns in the air)… quick, like lightning. Or “barurra”, the word for a red kangaroo, the anatomical characteristics of the kangaroo have inspired this contemporary movement: staunch and powerful with muscular shoulders and elongated torso… very intimidating when threatened. Even being sick, there’s this impulse, we say ‘wiibi-li’, so I used that rhythm, those three beats, and did a movement like this” – Leslie’s torso ripples as though something is propelling upwards and out. “So it’s all very contemporary. They’re not cultural steps because I haven’t been trained in cultural dance. My style comes from the athleticism of the training I’ve had in African-American contemporary dance. So I’ve drawn from the rhythm and meaning of Gamilaraay language to create these steps. For me it’s saying to Ian and other young people, ‘Look into your culture.’ And we’ve also drawn from Ian’s Noongar dance knowledge and technique. He and I have collaborated in making another vocabulary for this production.”

The concept of reclaiming language has extended beyond the creation of this work, adds Howett. “Daily dance class is all in Noongar,” he notes. “What I find interesting is seeing Michael’s way of bringing his dance background and cultural background together to say, ‘This is who I am, and this is what I think about things.’”

Top photo: Ian Wilkes and Michael Leslie in ‘3.3’. Photo: Mark Howett.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.