Review: Tempest Theatre, Sparrow by Susie Conte ·

Subiaco Arts Centre Studio, 3 May ·

Review by David Zampatti ·

There’s something of Albert Facey’s widely-read autobiography A Fortunate Life about Tempest Theatre’s neatly drawn and revealing portrait of the West Australian writer and nurse Mollie Skinner.

Like Facey, Skinner’s life was, to all appearances, far from fortunate. She was “homely” (as the euphemism of the time put it), scarred by a cleft lip and afflicted for years with bouts of blindness caused by an ulcerated cornea. She remained single through her life but struggled with it; she was attached to her mother and two brothers and grieved for their misfortunes and loss (one brother, Bob, was killed in World War I but his body remained missing for a decade; the other, Jack, was terribly disfigured by a wound to the jaw).

Still, she did great work as a nurse and midwife in India and Burma, and in the remote WA bush.

And she wrote. But Skinner may have remained unknown and the story of her life untold were it not for a chance meeting at a boarding house she ran at Darlington in the Perth Hills.

That encounter was with the visiting DH Lawrence, and their brief association had far and long-reaching consequences for Skinner; the unlikely connection she made with the famous and infamous writer led to a collaboration and friendship that lasted until Lawrence’s death eight years later and resulted in one book (Skinner’s The Boy in the Bush) and provided inspiration for another (Lawrence’s Kangaroo).

Eventually, at the end of her life, Skinner wrote an autobiography, The Fifth Sparrow. Along with archival material, this text has been fashioned into a modestly staged but impressive monologue by Susie Conte, who also performs as Mollie, with audio-visual design by Tess Metcalf and Kylie Maree (an earlier production of the play was performed by Maree and toured to US fringe festivals).

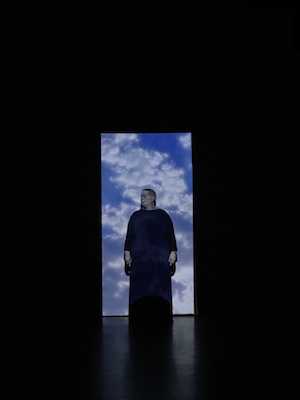

Conte gives an unhistrionic performance that pays respect to her subject and her concerns – the place of women in the world, the nature of love and its lack, the impulse to art. It is well, and sometimes beautifully, supported by a simple, austere design upon which Metcalf and Maree throw impressive visual effects, complementing the narrative without distracting us from it.

Sparrow is a well-constructed and enlightening window into people and times that have faded from memory. It’s good to have this chance to see them again.

Top: Susie Conte in ‘Sparrow’.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.