The appointment of Iain Grandage as artistic director of Perth Festival for 2020-2023 received a highly enthusiastic communal thumbs-up when it was announced earlier this year. Grandage will be speaking at the Blue Room Theatre, Saturday 4 August, but Nina Levy decided to sneak in a pre-show chat.

When acclaimed composer Iain Grandage was announced as Perth Festival’s artistic director for 2020-2023, back in May, there was a palpable buzz of excitement in the WA arts community. It was immediately clear that people feel a sense of connection with Grandage. While this communal stamp of approval can be attributed, in part, to the fact that he’s a local (raised and trained in Perth), I believe there’s more to it than that. Grandage has composed and played across numerous art-forms – opera, theatre, dance – with the result that he has the affections of an unusually broad range of arts-enthusiasts. He has won numerous awards for his work as a composer and music director, including an impressive seven Helpmanns for his compositions for theatre (Cloudstreet, The Secret River), for dance (When Time Stops), for opera (The Rabbits with Kate Miller-Heidke), for film (Satan Jawa, with Rahayu Suppangah) and as a music director for Meow Meow’s Little Match Girl and The Secret River.

Personally, I first came across Grandage’s work back in 2006, at the Perth International Arts Festival (now Perth Festival). He had composed the scores for two dance theatre works presented at the Festival that year, Steamworks Arts’s The Drover’s Wives and Splinter Group’s Lawn. Rich soundscapes packed with drama, both scores seemed, to me, inseparable from the action, inextricably linked to the movement on stage.

Twelve years later, then, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to talk to Grandage and find out about the process behind such compositions. When he picked up my interview call with a short song of greeting, my happiness was complete, in the manner of a teenager who has just acquired the autograph of her favourite pop star. Suffice to say Grandage is a delightful mix of creativity and general niceness.

Originally from Brisbane, Grandage moved to Perth with his family in the mid-1970s and began his formal music training shortly after, starting piano lessons at age seven and cello at ten. Although he gave up piano at 13, he continued to play the instrument for pleasure. “I’d go to the music library and get books and books of pop songs, lots of stuff from the ’20s and ’30s… I don’t know why, I was really drawn to it,” he reminisces. “My dad’s dad was a linguist but also, as many people were back then, a composer. Because there were pianos in so many rooms, there was that great flowering of popular music that happened between the wars. So my grandfather, who my dad never even knew (he died when my dad was three months old), is a published composer. I often heard my dad play that piece and was drawn to music of that period.

While Grandage initially dreamed of playing in a piano bar, on acquiring such a job, at age 18, he discovered that it was “one of the loneliest things you can ever do in your entire life.” By comparison, he found the cello much more sociable. “Once I started the cello, within a year I was in the junior orchestras of the West Australian Symphony Orchestra,” he remembers. “That became [the source of] my closest friendships and so much of my social life revolved around holiday music camps and Saturday morning music-making. At that time Richard Gill was here, running the music part of WAAPA (the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts) and he also started a thing called Junior Exhibitioner Course, on a Friday afternoon. That was a collection 30 of us who did aural training, choir, performance practice and stylistic composition. It was revelatory for me. So that was my Friday afternoons and Saturday morning was orchestra. Very quickly, music was a large part of my social and extra-curricular life.”

Despite this, Grandage wasn’t planning to become a professional musician when he finished school. “I went to UWA because I wanted to be a lawyer, actually,” he tells me. “In those days you had to do a year of another degree before you went into law. I did music for that first year. For many years I had a great sadness that the university, at that stage, didn’t offer a music/law degree. They since have and I think I would have grabbed that with both hands because I love words, I love the power of words.”

What changed his mind?

There were two factors, he replies. “Firstly, I had a brilliant time in the music department at UWA. I fell in love with the fact that that music wasn’t just on the weekends, that you could do it day in and day out.

“Secondly, I read Albert Camus’ L’Étranger (The Stranger), in French literature class, and that was about a lawyer who failed his clients. I now know I was ill-informed but I saw that law wasn’t always utilised for good and that confused me. I thought that was all law. Now I see all the avenues by which law is an incredible tool for helping society. You see it standing up to Trump, to Farage, closer to home, to Dutton and various elements. I’m a huge supporter of the power of the judiciary. That’s a tangent, isn’t it? But, fundamentally, it was an affirmative choice towards music rather than a negative one away from law. It was more ‘I can’t help but continue doing this.’”

Fundamentally it was an affirmative choice towards music rather than a negative one away from law. It was more ‘I can’t help but continue doing this.’”

Grandage admits that during his 20s he had moments of questioning that choice, when struggling creatively or financially. Ultimately, though, he says he has no regrets, perhaps because of the eclectic nature of his career path. “I chose to move out of being purely a cellist and into other performing arts, writing music for theatre, and from there into dance, and from there into graphical music, and from there into opera,” he elaborates. “Each of those informs the other and you don’t need to get too stymied by one of them or too dulled by your experience with one of them, because the next is helping to change things up.”

Grandage made that move away from being a “straight” cellist and into other art forms relatively early in his career. “In 1995 I auditioned to be an actor in a Black Swan show, a piano accordian player in Louis Nowra’s Cosi. That was the first time I met [Black Swan director] Andrew Ross and we really hit it off. He’s a glorious human who has a wicked sense of humour and an immense brain, and intrigue about what is possible in storytelling in the arts. I said to him, ‘I’m a particularly shit actor,’ but despite that he still cast me.”

In fact, he told Ross, his real interest was composing music for shows, a confidence that paid off. “I did most music for most Black Swan shows from 1995-2000 and that was a great training ground,” he says. “In the midst of that, in 1997, Black Swan put me forward to do the music for Cloudstreet, the theatre production, with Australia’s finest director, Neil Armfield. At that stage, as a 26-year-old, I wouldn’t have had a look in, in terms of getting to work with him, except that it was a co-production between [Sydney-based] Company B Belvoir, which was Neil’s company, and Black Swan. So I got the entrée into the East coast theatre scene at the very top of the tree, which was a complete blessing.”

“After I did those five years with theatre, I was slowly finding my compositional voice and a series of opportunities came up with West Australian Symphony Orchestra, and in various contexts, for me to be an art music composer, writing for symphony orchestras and choirs. It was essentially sitting in a room and delivering scores, in that old school traditional way of notating everything, then you deliver it, rehearse for two days and perform,” he explains. “The worst thing [about working in that context] was the fact that I like people. Fundamentally, it’s an incredibly isolated and isolating experience, creating music. It’s like being a painter or a sculptor or a novelist. It’s a solitary creative pursuit.”

Being an old school, traditional composer is like being a painter or a sculptor or a novelist. It’s a solitary creative pursuit.

Working across disciplines is different, he explains. “I enjoy the fact that, when writing for a collaborative medium like theatre, you can either improvise in the room and you know it’s right because you’re making it up as you go, and you can read the feeling in the room, but also, if you go home and write something, you can bring it in and go, well that doesn’t work, and you can change it instantly. The feedback is far more immediate. I find many brains are far more powerful than one.”

Being from a dance background myself, I’m particularly interested to learn more about the way Grandage works with choreographers. “Perhaps my favourite dance experience was working with Gavin Webber and Grayson Millwood [Splinter Group, now The Farm] on a show they made called Lawn,” he muses. “The theatre environment Webber and Millwood create, the meta staging, the mis en scene is so clear, that whether you’re talking about an external world filled with banalities or an internal world filled with emotional complexities, it makes a very clear distinction about what music to do when. In those internal worlds, we’d essentially both launch from same moment. I knew that the arc of their dance would be, [for example], between four and four and a half minutes. I would write an arc of four minutes that made complete musical sense, and that was consistently evolving and making an argument and coming down to a logical conclusion around four minutes and then going into a kind of a loop, so that if they’re having a ‘tired old man’ day, they’re safe, the music’s not going to finish. [Working] in this way gives you immense freedom as a composer because you can make an argument…that is, in and of itself, musically satisfying. You can then layer other things on top of that broad arc that then speak specifically to any particular movements that they’re doing.”

“Then there are other scores, where I’m playing live. Another favourite score was for When Time Stops [by Natalie Weir, for Expressions Dance Company], with a much-loved band of fellow musicians from Queensland called the Camerata of St John’s. They played live on stage and were just so fantastic and courageous in how they stood amongst fast-moving dancers and memorised huge slabs of the score. It was such a thrill. That was an instance where I essentially wrote a score [and brought it to the choreographer] and for Natalie, who is a far more traditional choreographer, that worked very well.”

Essentially, says Grandage, the key factor in successful collaboration is that all artists have freedom of expression, but also clearly defined artistic aims. “When you’ve clearly discussed the [ground you want to explore] before you leap in, then you know that what you deliver is going to be on the same page. Those collaborative projects are a great joy.”

I love the idea of sewing these disparate lines together to make a festival that’s actually euphoric and filled with hope, and filled with a celebration of us in this place.

Grandage directed the Port Fairy Spring Music Festival from 2016-2018 and, listening to him talk about collaboration across art-forms, it’s easy to picture him in his upcoming role of Perth Festival artistic director, directing across disciplines. “I’m very attracted to the act of storytelling,” he agrees. “Something that occurred to me across my time running the Port Fairy Spring Music Festival is the fact that you can make statements about society and hopefully make a small change for people by presenting a whole series of works that talk to each other and are beyond the creative powers of any single artist. In curating that small festival and now with the chance to curate this big festival you can program people with bigger brains than your own, who have ways of the viewing some of the intractable problems that face us as a society, but also those things that celebrate the great shared moments of humanity in ways that you find unexpected and joyful and never would have thought of yourself. So you can make a bigger statement, and make more of a difference.

“It feels like a way of – just like when I am writing a piece of music – synthesising a whole pile of different lines together into a coherent whole. The whole idea of a conversation happening inside a piece of music is the same transaction as two large scale works of art being placed next to each other, having that same conversation. The way you stimulate an audience’s mind is the same, inside a festival program. You’re going, ‘See that… and now see this!’ It’s the same as having two vastly different musical voices sitting cheek by jowl inside a piece of music. I love the idea of sewing these disparate lines together to make a festival that’s actually euphoric and filled with hope, and filled with a celebration of us in this place. It’s a glorious part of world and I want to celebrate it with every fibre of my being.”

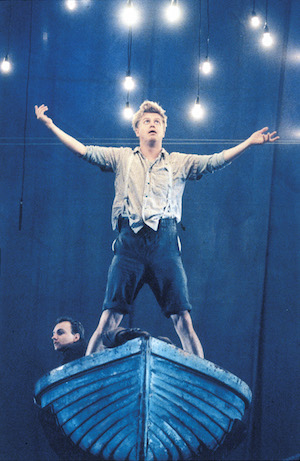

Iain Grandage is pictured top. Photo: Rhys Woolf.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.