Review: Tarsh Bates, “This Mess We’re In” ·

Old Customs House, Fremantle ·

Review by Jenny Scott ·

At the junction of science and experimental art, the works within “This Mess We’re In” explore big ideas – specifically, queer and intersectional feminist perspectives on the relationships between life and technology. The first curatorial project of Perth-based artist Tarsh Bates, this exhibition is presented as part of “Unhallowed Arts”, a program of events organised by SymbioticA to celebrate the bicentenary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Bates has taken Shelley’s text as a starting point to navigate the implications of, and ethics surrounding, the impact of science upon our bodies and bodily experiences. The diverse works in this sprawling survey – which range from a hypertext novel to a family tree of yeast samples – span fields such as biotechnology, speculative design and queer theory in order to critique colonisation, the patriarchy and scientific paradigms all within the context of the Anthropocene.

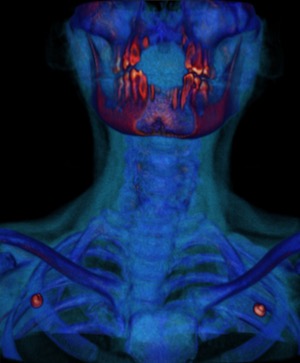

Many of the works in this exhibition implicate the artist’s own bodies, often in invasive and confronting ways. In the video work Transplanted (2018), Karen Casey utilises her own medical scans, generated during the process of her recent liver transplant. This video work is at once deeply personal and strangely abstracted, as the clinical lens of medical imaging strips Casey’s body back to its component parts. Observing the artist purely as a physical specimen, the viewer must assume and reinsert the emotional trauma and suffering felt during such a dire crisis of health.

Elsewhere in the show, Hege Tapio’s slick trade fair display showcases a series of smartly packaged resin cubes containing “HumanFuel”. The accompanying brochure reveals this substance to be a biofuel distilled from the artist’s own body fat, which was obtained through liposuction. Using a cosmetic surgical procedure to harvest her own body, Tapio has produced a deeply disconcerting product which works to problematise the nature of fossil fuel alternatives. Nearby is Abhishek Hazra’s Let a Thousand Proteins Bloom (2011) in which the artist has extracted ammonium nitrate (used in both fertiliser and explosives) from human breast milk. Both Tapio and Hazra utilise chemistry to interrogate the politics of women’s bodies, challenging gendered ideas of utility, purity and labour, on an industrialised scale.

A significant proportion of the works in “This Mess We’re In” tackle this sort of heavy subject matter with a tone of irony and humour – such as Kathy High’s OKPoopid (2017) in which the artist, who has Crohn’s disease, uses speed-dating to search for “the perfect poop partner” for a faecal transplant.

Other works combine satire with a reconceptualising of ecological crisis – Mike Bianco’s The Bush Blaster (2017), a preposterously phallic strap-on purportedly designed to assist honeybees with pollinisation, skewers aggressively masculine conceptions of the natural environment. In The Molecular Queering Agency (2017), Mary Maggic encourages a radical rethinking of the ongoing pharmaceutical contamination of our environment. A kitsch, retro-futurist video implores us to embrace the “queer possibilities” of this toxicity, reframing the pollution as an opportunity for us to consider our bodies as “permeable, mutable, changeable and disobedient”. This video is paired with a set of oxygen masks attached to vials; artefacts from a live performance in which hormones are extracted from the urine of participants, who then inhale the hormones of previous users. It’s a clever, and entertaining, work of experimental art (but definitely not for everyone).

It’s well worth purchasing the exhibition catalogue to learn more about each artist and their practice, particularly as the elaborate, labour-intensive complexity of some of the works is not immediately apparent. The stippled illustrations of mutant creatures produced by Svenja Kratz seem relatively straight-forward, until you discover that the inks were created from “genetically engineered protein mutant pigments” produced through a process of mutagenesis. Nevertheless, other works are equally affecting in their simplicity – such as Kirsten Hudson’s abjectly huge sugar cubes, each weighing as much as the artist, or the meditative labour depicted in Katie West’s grinding stone video.

A significant amount of time is definitely required for visitors to adequately explore the depths of this dense exhibition. Confronting, beautiful, and often bizarre, the radical works of “This Mess We’re In” offer a lot to consider and will stay with you long after your visit.

“This Mess We’re In” closes November 2.

Pictured top: Kirsten Hudson’s abjectly huge sugar cubes.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.