We are living in strange times but Iain Grandage’s debut program for Perth Festival provides a sense of hope. Nina Levy spoke to the Festival’s new artistic director about the 2020 Perth Festival line-up and the principles underpinning his curatorial choices.

It’s a Thursday afternoon at Perth’s Government House Ballroom and, while the rest of us are enjoying afternoon tea in celebration of Barking Gecko Theatre’s 30th anniversary, Iain Grandage is playing the grand piano with his customary verve and vigour. Accompanying Jessica Hitchcock as she sings “Where?” from The Rabbits, his pleasure is evident… as well it might be given that he was musical director, musical arranger, and composer of additional music for this award-winning work of operatic theatre. There’s something pleasingly circular, too, about watching Perth Festival’s new artistic director play a piece from a work that had its premiere at the 2015 Perth Festival.

For me, though, this performance is particularly delightful because it takes place just hours after I interview Grandage about his debut Festival program.

That’s the thing about Iain Grandage. An acclaimed composer, musician and music director, he doesn’t just talk the talk. And the walk he walks traverses a broad range of genres – in addition to his concert works, he has composed for theatre, dance, opera and film.

So I open my embargoed copy of the 2020 Perth Festival program with no small degree of anticipation. I’m excited to see what music treats are in store, of course, but I’ve high hopes across the board, given the breadth of Grandage’s creative endeavours. In particular, knowing his history of collaborating with choreographers, I can’t wait to see what he has planned for my not-so-secret first love, dance.

And I’m not disappointed. Soon I am emitting little involuntary squeaks of excitement as I discover an enticing mix of works I know of and have been longing to see, works I don’t know of but sound right up my alley, and new works from a selection of my favourite local companies.

The most significant and welcome surprise, however, is not about any particular genre. It’s the pages and pages of the program that are dedicated to work by First Nations companies and artists.

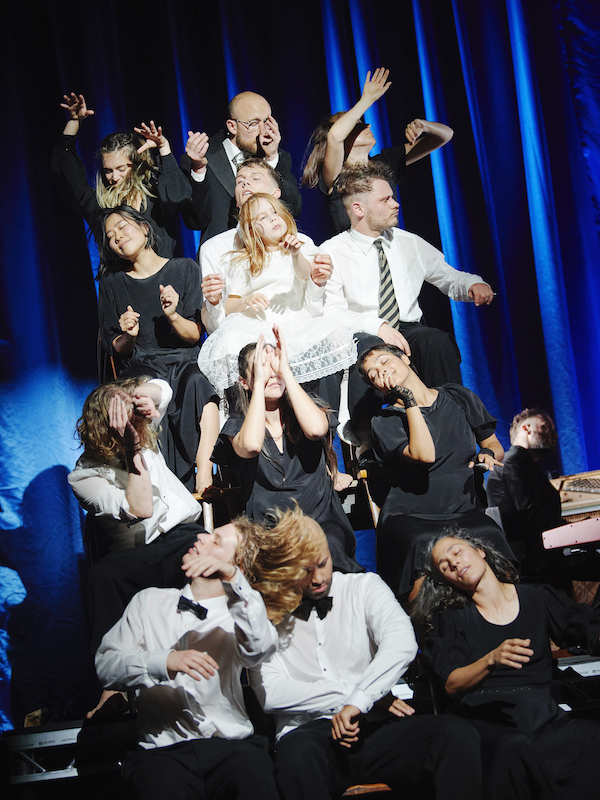

In fact, in a first for any major Australian international arts festival, the whole of the first week of Perth Festival is dedicated to First Nations performances. There’s Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company’s Hecate, an adaptation of Macbeth written and performed entirely in Noongar language, and Bangarra Dance Theatre’s critically acclaimed Bennelong, which explores the legacy of the iconic Woollarawarre Bennelong. There’s Black Ties, a comedy about a Maori and Aboriginal couple’s wedding party, by ILBIJERRI Theatre Company and Te Rēhia Theatre. There’s the much-anticipated remount of Jimmy Chi and Kuckles’ Bran Nue Dae by West Australian Opera. And there’s Buŋgul (pictured top), which draws audiences into the culture that inspired Gurrumul’s final album, Djarrimirri (Child of the Rainbow) and is performed by Yolŋu dancers, songmen and the West Australian Symphony orchestra.

And that’s just the first week’s offerings – there are works by various local and interstate Indigenous artists throughout the Festival.

That imperative, to showcase the work of Aboriginal artists, is embedded not just in the Festival’s programming, but in its staffing, explains Grandage, with Kylie Bracknell appointed as the Festival’s Associate Artist, and an Indigenous Advisory Group that includes Vivienne Hansen, Mitchella “Waljin” Hutchins, Carol Innes, Barry McGuire, Richard Walley OAM and Roma “Yibiyung” Winmar.

“It feels lovely to have someone like Kylie Bracknell as my artistic associate … by way of indicating how central the Indigenous cultural bedrock of this place is to us being able to exist here happily,” remarks Grandage. “That’s both in staffing terms, but also in programming terms for 2020. If you’re going to do a festival about place, then you’ve got to acknowledge the ground on which you stand. This 2020 festival is a celebration of this place and the people of this place.”

“If you’re going to do a festival about place, then you’ve got to acknowledge the ground on which you stand. This 2020 festival is a celebration of this place and the people of this place.”

It’s Bracknell who is writer and director of Yirra Yaakin’s Hecate, a work that has been seven years in the making. “Why Shakespeare? It took me a long time to reconcile that,” Grandage reflects. “But Shakespeare was responsible for this immense explosion in the English language. The parallel for that – this bringing back of Noongar language to its rightful place, speaking the stories of the country – feels so beautiful. There are no subtitles or surtitles in Hecate, just these slides between scenes, describing what’s going to happen and then you get to exist completely inside the poetry, the phonetic beauty of this language.”

Beautiful it may be but Hecate is also inextricably linked to the trauma that led to the loss of language in the first place, as Grandage is well aware. “The older generation, especially, were not just passively denied but actively denied their language for decades and generations, because of the effectiveness of AO Neville as the chief protector of Aborigines. For them to then hear their language celebrated on stage for an hour and a half … that will bring up trauma and grief for those people who were denied language.”

And so, Grandage continues, Bracknell has created Hecate Kambarnap to run before and after Hecate. “Kambarnap” means village, he explains, and the initiative provides a place of care and support for anyone who needs it. “Kylie’s been pushing this very hard, that it’s imperative that there’s a place for people to start to process that grief. And that place is this campfire that sits outside and burns for the duration of the season, and it’s a place for counsel and for support and for cleansing.”

Acknowledging and celebrating First Nations culture is not a new goal for Grandage. As artistic director of Port Fairy Spring Festival he began programming “Quartet and Country” – a series of commissions that sees Indigenous composers invited to compose for the Australian String Quartet – back in 2016. Five years later he’s bringing the project to Perth Festival and is collaborating with Roma “Yibiyung” Winmar on one of the pieces that will be performed on the program.

“I’m a classical musician who was always aware that the legacy of Western art music, quite clearly, emanates from Europe,” he reflects. “And it’s a very European legacy. And there were people like Peter Sculthorpe, Ross Edwards, who, in the generation of composers before me, spent their time trying to successfully finding ways of making Australian creative expression. But for me, the fundamental Australian creative expression lies inside Indigenous composers and [‘Quartet and Country’] is about resourcing those composers so that they get to write for the Australian String Quartet and bring those songlines into conversation with Western art music.” The composers on the Perth Festival iteration of “Quartet and Country”, says Grandage, will represent the four corners of the country. “Lou Bennett is Yorta Yorta woman, Dja Dja Wurrung, from Victoria. William Barton is a Kalkadungu man from Mount Isa. Stephen Pigram is a Yawuru man from Broome. And Roma Winmar is from this corner of the country.”

At the same time, says Grandage, collaborating with Indigenous composers has inspired him to question where his own ancient stories lie. “And those questions inevitably get answered in the West Country of Ireland and in those places of the ginger beard,” he says with a smile.

That’s where works like Cloudstreet, the stage adaptation of Tim Winton’s classic novel co-produced by Black Swan State Theatre Company and Malthouse Theatre, and Michael Keegan-Dolan’s dance theatre work Mám, come in to this year’s Festival program. “Tim Winton calls himself ‘desert Irish’, but also has a strong connection to Noongar Boodjar in something like Cloudstreet,” muses Grandage. “And I’ve invited Michael Keegan-Dolan [whose company Teac Damsa performed Swan Lake/Loch na hEala at last year’s Festival] back with his brand new work called Mám, which is built on the far West coast of Ireland, the top of the Connor Pass, looking out west – as we do – across the ocean.

“This dance is really earthed … not unlike the earthed nature of Bangarra Dance Theatre, but also Michael is aware of the effect of colonisation on the Irish – even though it happened centuries before the experience of our First Nations people – and that’s rendered in this particular piece by an act of exquisite beauty. So there’s Cormac Begley, who is a fourth generation squeezebox player and he plays the first 25 minutes of the show… just him on various squeezeboxes with these twelve dancers going wild, such an amazing kind of rendering of place and of collective ownership. And then a curtain slides pass and there is the eight-member European orchestral ensemble s t a r g a z e, and this fiddle player starts to play this Telemann solo sonata, exquisitely, like some of the finest fiddle playing I’ve ever heard. All of the dancers are rendered immobile and silent. And Cormac just sits there; they all stare at this single fiddle player. I’ve never seen a more potent rendering of colonial dominance on a stage; often you see it in acts of violence, but this is the beauty of a single violin, bringing centuries of tradition with it, but then the silenced millennia of tradition from those people … it’s such a moment and this show is filled with those sort of moments.”

Like his immediate predecessor, Wendy Martin, Grandage feels strongly about the importance of programming local artists alongside international acts in the Perth Festival line-up, and of providing opportunities for local artists to rehearse and perform alongside visiting artists. One of several examples of such opportunities is “Ancient Voices”, which will see UK six-part vocal ensemble The Gesualdo Six, a group “at the very peak of their powers”, joined by 34 singers from Perth choirs The Giovanni Consort and Voyces. “They’ll be singing – on the 450th anniversary of its being written – the Thomas Tallis Spem in Allum, which doesn’t very often get heard,” says Grandage. “It will be sung in the round, in Winthrop Hall, so that audience is in the middle, surrounded by a 40-part choir.

“And then matching that will be a piece composed and performed by [virtuoso didgeridoo player] William Barton. So you have this 450 year old tradition, which we think of as very old in Western musical terms, alongside a thousands-of-years-old tradition brought by Will and his yidaki and the work that he’s written for Voyces. And then, those old songs will be brought into a conversation with two works by West Australian female composers, Olivia Davies’ Lux Aeterna and a new commission by Cara Fesjian, based around Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. It’s a thrill to have all of those things [in one program].”

“I’m very interested in this idea of the power of the many over the demands of the few. It feels utterly of the moment you know, as you look at the rise of the strongman in politics.”

Such collaborations between local and visiting artists will also be seen in dance and circus, Grandage continues. Stephanie Lake’s Colossus, which premiered in Melbourne last year to critical and popular acclaim, sees fifty bodies converge on stage. For the work’s Perth Festival season dancers will be sourced from WA’s Strut Dance and the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, giving these artists the opportunity to work with Melbourne-based Lake and her company. Strut Dance will also present “Hofesh in the Yard” in collaboration with Hofesh Shechter Company, allowing 12 independent dancers from across Australia and the Asia-Pacific region a chance to perform two works by this seminal UK-based Israeli choreographer, Uprising and tHE bAD. “Seeing Uprising, a decade ago, was the moment that I fell in love with Hofesh Shechter,” recalls Grandage. “Having that work built on Australian bodies feels like a wonderful way of not only having Hofesh with us but but also making a difference to artists.”

And then there is Leviathan, a new work by Brisbane’s Circa that will make its world premiere in Perth. “Leviathan is being built on West Australian bodies, with all 18 members of the Circa ensemble, alongside six dancers from WA’s state flagship contemporary dance company Co3, six circus performers sourced through WA’s Circus Maxima and Circus WA, and six children who are also circus performers,” Grandage tells me. “So there’s 36 people on stage. I love this. I love seeing masses of bodies on stage, it feels very special and it’s actually something that the Festival can do that local companies rarely get to do.”

For Grandage, such large-scale shows have a particular relevance at this moment in time. “Not only are you making an impact on the artists involved, like those 50 dancers inside Colossus, but also for the audience there’s quite a thrill about seeing the power of that collective, and I’m very interested in this idea of community,” he reflects. “I’m very interested in this idea of the power of the many over the demands of the few. It feels utterly of the moment you know, as you look at the rise of the strongman in politics – and they are men – and that issue of, not only trying to right that gender imbalance but also, as described in Indigenous wisdom, it’s the circle way. It’s the power of the of the many to make a broader and more lasting influence than the demagoguery or instruction of the single.”

Amen to that.

Perth Festival runs February 7 – March 1, 2020.

Head to www.perthfestival.com.au to check out the full program, which includes performance, music, visual arts, the Chevron Lighthouse, literature and ideas and Lotterywest films.

And stay tuned for more Seesaw features about Perth Festival over the coming months.

Top: ‘Buŋgul’ draws audiences into the culture that inspired Gurrumul’s final album, Djarrimirri (Child of the Rainbow). Photo: Jacob Nash.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.