Mark Naglazas discovers everything old is new again as he reconsiders films from the past.

Drawing comfort from nostalgia

9 April 2020

- Reading time • 10 minutesFilm

More like this

- The great unknown

- Darkness lights the way

- Shining a beacon of light on our history

It’s often said that in dark times Hollywood and movie audiences in general embrace nostalgia. When faced with war, economic downturn and social disturbance we rush to settings and stories that take us back to an imagined simpler time. For example, in 1969, when America was reeling from mass demonstrations, the Vietnam War and the Manson murders, the top film at the US box office was the Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

I’m sensing that rush back to older movies is happening in the Age of Corona. Television is now flooded with older movies — Stanley Kubrick’s great epic Spartacus made a surprise appearance recently — and social media is full of people talking about their favourite movies of all time, recommending little-seen gems, posting trailers of classics and asking for help to find movies they love but are difficult or impossible to find. Everything old is new again.

For me it is a chance to revisit films that I love and deepen my connection to them. Great films have such power to sweep you up that you often don’t know what makes them so special to you. And watching in a case of global emergency they can reveal different meanings, which happened to me during a second look at a film I loathed the first time around, The Wolf of Wall Street. It feels like the right thing to do in this time of reflection and reconsideration.

An Officer and a Gentleman (Netflix)

Everybody knows this 1982 naval school romantic drama from the famous scene in which a newly graduated Zack Mayo (Richard Gere) rides his Triumph Bonneville to a factory in which the woman he spurned for his career (Debra Winger) works, sweeps her into his arms and carries her into an uncertain future (beautifully parodied on The Simpsons when a Zack-like Homer declares “I’m going back to the backseat of my car and I won’t be back for ten minutes!”). However, the cheese of the these final moments doesn’t overwhelm what is essentially a brilliantly constructed, powerfully performed drama about the son of a lowlife sailor fighting to overcome trauma and mistreatment (a mother who killed herself, a brutal, unloving father) not by fleeing military service but diving back in and proving himself worthy to be “an officer and a gentleman”. Gere has never been more charismatic as the kid from the streets who battles Lou Gossett Jr’s foul-mouth, hard-arsed sergeant — the midpoint training confrontation is one of the great moments of 80s cinema — and the great Winger brings warmth and spontaneity to factory worker Paula who acts out of pure love. An Officer and a Gentleman is a romantic classic but one underpinned by so much trauma and tragedy that its fairy tale ending is well-earned.

Inside Llewyn Davis (Stan)

Everybody has their favourite Coen brothers’ movie. For many it is the pitch-black crime drama (Blood Simple, Fargo, No Country for Old Men), for others it’s the goofball comedies (The Big Lebowski, O Brother, Where Art Thou?). But for me — lover of the entire Coen oeuvre — it’s a movie unlike any of their previous work, Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), that now sits atop perhaps the greatest body of work in contemporary American cinema. This fable about a good but not great folk singer (Oscar Isaac) struggling for recognition in Greenwich Village in the early 1960s is so heartfelt and touching, despite several bleakly comic twists, you have to check it’s from the brothers who normally take such wicked delight in watching the damned fight their dreadful fates. What is typical of the Coens is their loving recreation of the era, with cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel giving us such a rich palette of blues and greys that it evokes every New York flick of the 60s and 70s. And the performances of folk and faux musical classics is so stirring you’ll want to Spotify the era and the genre the moment the credits roll. When we finally get to hear Llewyn sing Fare Thee Well we realise that talent and success are not natural bedfellows. That’s the tragedy. And it’s what makes Inside Llewyn Davis so deeply moving.

Sullivan’s Travels (iTunes)

In the early 1940s Preston Sturges had one of the greatest runs in American film history, writing and directing a string of screwball comedies that have come to define the cockeyed optimism of mid-century America. The greatest of them is Sullivan’s Travels, an hilarious and, at times, dark and troubling tale of a big-shot director of blockbuster comedies who wants to make a meaningful film in the mould of Frank Capra. The problem is that the eponymous John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea) knows nothing of the suffering Americans outside of Hollywood. So he dresses himself as a bum and sets out discover the real America, an marvellously madcap adventure that sees Sully accused of murder and rotting in a chain gang. The opening dialogue of Sullivan’s Travels is some of the smartest, funniest, sharpest writing in the history of film (dammit, the history of writing!). And the relationship between Sullivan and Veronica Lake’s embattled but chipper actress is as sparky as it is touching and romantic. The climax, in which Sully rediscovers his soul and purpose as a popular entertainer, will leave you gasping for superlatives. A film about the Depression years that will not leave you depressed.

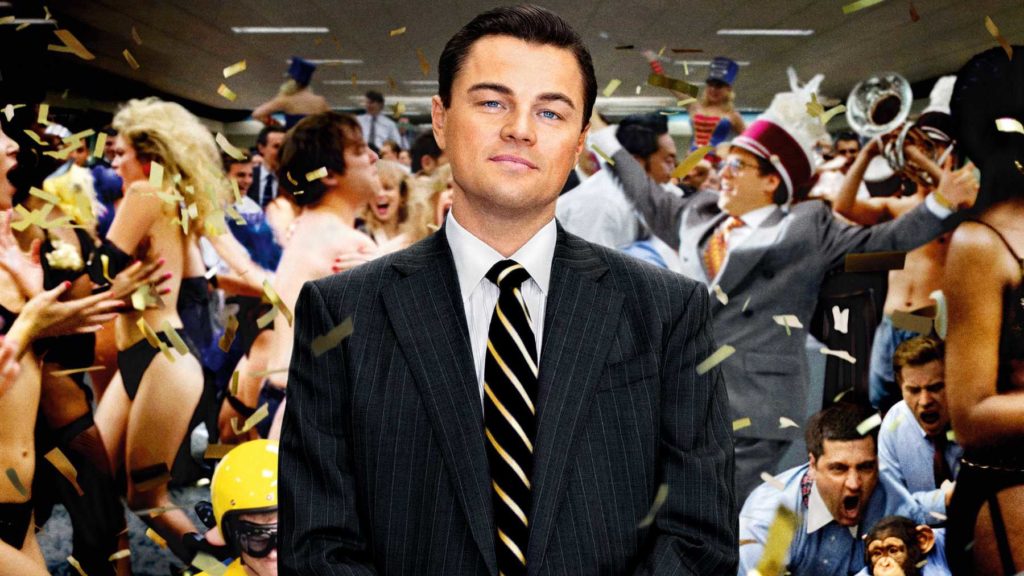

The Wolf of Wall Street (Amazon)

I’m a huge fan of Martin Scorsese, the giant of post-1970s American cinema. But I must admit that when I first saw his 2013 black comedy centred on Wall Street excess and criminality it left me cold. It felt like an excuse to uncork the worst male behaviour imaginable (today we call it “toxic masculinity”) instead of being a cold-eyed analysis of a dark chapter in American financial history. But re-watching The Wolf of Wall Street as capitalism is reeling from the biggest shake-up since 1929 it has acquired a meaning I struggled to find the first time round. Leonardo DiCaprio’s coke-snorting, hooker-humping, money-grubbing stockbroker Jordan Belfort seemed that much more pathetic despite his enviable lifestyle, and the corruption of his employees more loathsome and destructive. And it’s truly hilarious. Jordan’s Quaalude-fuelled sportscar ride is not just a classic comic scene but emblematic of an era of mass delusion. Scorsese’s ability to conjure an on-screen energy is in full cry, DiCaprio’s talent for mania has never been more amusing and, of course, The Wolf of Wall Street gifted the world Margot Robbie, an old-school bombshell who has proved time and again that she can act. If The Irishman (Netflix) is too forbidding go back to Scorsese at his most impish and electrifying.

Private Life (Netflix)

This heartfelt dramedy about a middle-aged New York couple desperate for a child is only the third film by writer-director Tamara Jenkins in two decades despite her previous features, The Slum of Beverly Hills (1998), The Savages (2007), earning huge acclaim. It’s a shame Jenkins has not worked more frequently because on the evidence of her latest comedy-drama she is one of the most astute observers of middle-class aspiration in American cinema. The first half of Private Life (2018)deals with theatre director Richard (Paul Giamatti) and his novelist-wife Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) going through IVG and failing to get pregnant. Their solution is to ask the uni student daughter of a friend (Kayli Carter of Godless fame) to donate an egg, a desperate act that brings Richard and Rachel into the orbit of a lost but unnervingly confident millennial in whose hands their future happiness lays. Jenkins went through the process herself so Private Life feels painfully real, with curious procedural details popping into every beautifully wrought, funny-sad scene. There is added poignancy to the many Woody Allen-ish walk-and-talk street scenes, with Manhattan bursting with the life that Richard and Rachel are trying to create. Jenkins covers similar terrain to Noah Baumbach whose Netflix release Marriage Story makes a wonderful companion piece.

The Last Waltz (Amazon)

Music nostalgia has been just as strong during the pandemic as our desire to go back to old movies. So my heart skipped a beat when I discovered on a streaming service Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary about “the farewell concert appearance” of The Band, the Canadian-American group ranked amongst the most influential rock act of all time. Despite its reputation as the greatest ever documentary about a concert and my passion for Scorsese I’d somehow never seen The Last Waltz until recently. It was a revelation. Watching the way Scorsese and his team of ace cinematographers — amongst them Michael Chapman (Raging Bull), Vilmos Zsigmond (Close Encounters of the Third Kind) and Lazslo Kovacs (Five Easy Pieces) — capture The Band singing with many of the era’s greatest artists (Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan) I now totally understand its reputation. The warm, sensual lighting, the fluid non-invasive camera work, the beat-perfect editing make it a masterclass for anyone who wants to shoot a band in performance. And, of course, there’s the music. The Band were famed for backing Dylan. But when you watch and listen to Levon Helm singing Robbie Robertson’s classic “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” (yep, a Canadian wrote the famed Civil War lament) you’ll see a bunch of musicians worthy of standing not behind but beside Dylan.

Ninotchka (iTunes)

When the virus hit the first film I went back to this 1939 screwball classic about a Soviet operative (Greta Garbo) sent to Paris to sell jewellery confiscated from the aristocracy during the Russian Revolution. I was drawn to Ninotchka for a single scene, the moment when the playboy who seduces the dour Soviet operative away from her cause (Melvyn Douglas) attempts to make her laugh. Each of his jokes falls flat, with Ninotchka’s face as stony as Stalin’s. However, when Douglas’ Parisian playboy tumbles off his chair everyone in the café bursts out laughing, with the biggest guffaw coming from Ninotchka. It is one of the most joyous scenes in the history of movies, and the film was advertised as “Garbo Laughs” (it was a shout-out to the immortal tagline for her first talking picture, “Garbo Speaks”). Ninotchka was co-written by Billy Wilder, who later gave us such comedy masterpieces as Some Like It Hot and The Apartment, and directed by Ernst Lubitsch with all the polish evoked by his name (the famed “Lubitsch touch”). It is the perfect antidote to the plague of misery and despair engulfing the planet.

Pictured top: An Officer and a Gentleman: Richard Gere sweeps Debra Winger into his arms in a well-earned fairy tale ending.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.