Unlikely weapons have enabled a group of Martu artists to create a powerful and plaintive appeal for the protection of their Country from the threat of uranium mining. Craig McKeough reports.

Facing off mining giants with art

17 August 2022

- Reading time • 10 minutesVisual Art

More like this

- A walk with Tina Stefanou

- A blaze of glorious people

- Diving into the gothic world of Erin Coates

The battle by First Nations people for the right to determine how their traditional lands are used is often a lopsided one, especially when powerful mining and political interests tend to line up on the opposing side.

For the Martu people of Western Australia’s Pilbara, there are limited opportunities to make their voices heard amid the clamour about jobs and economic growth that resources projects bring.

But as the world’s biggest uranium miner continues to hold a potentially lucrative uranium deposit on a patch of ancient Martu country, a small group of traditional owners is raising awareness about their determination to reclaim their land with the aid of unlikely weapons – paint and canvas.

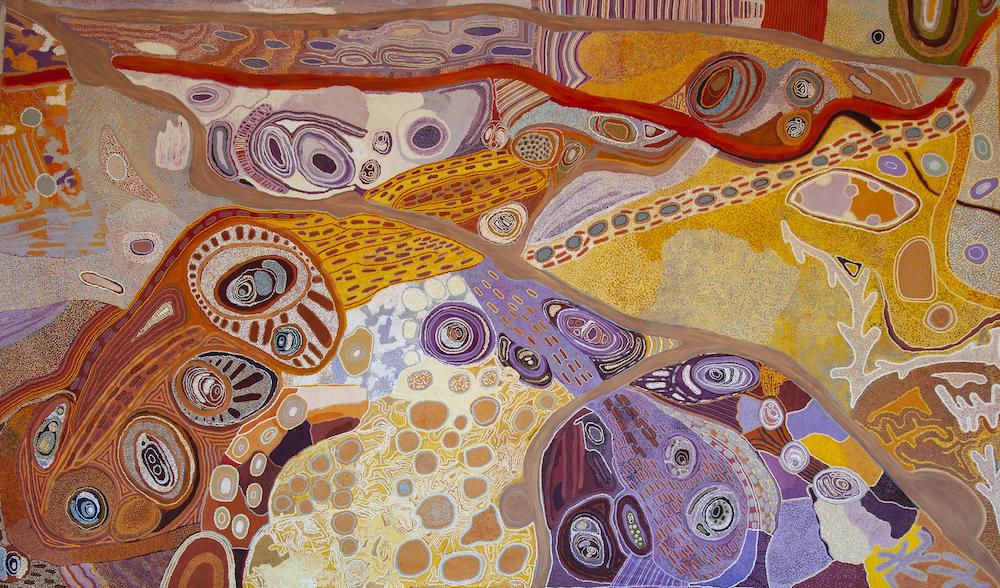

Kintyre, an acrylic painting on an epic five by three metre scale, is the result of a remarkable near two-year process of reflection, collaboration and storytelling by 23 artists across generations. It proudly proclaims: “We are Martu and this is our story.”

Kintyre is river desert country – parched land given life from precious water as the Karlamilyi River and other waterways carve through spinifex, rocky outcrops, lake beds, claypans and waterholes.

This is the heart of the east Pilbara, more than 300km from the mining centre of Newman and 1500km north-east of Perth. It is a traditional home for the Martu people who have a continuing culture and attachment to this land reaching back many thousands of years.

Disputed agreement

The Kintyre deposit borders Karlamilyi National Park – in fact it was carved out of the park by the State Government in 1994 when the value of the uranium became apparent. The miners who have laid claim to the deposit since 1985 – first CRA (a forerunner of today’s behemoth Rio Tinto) and since 2008 Cameco – have a chequered history of engagement with Aboriginal people. That engagement culminated 10 years ago with an Indigenous Land Use Agreement between Cameco and the native title representative body, the Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation.

“We are fearful of the uranium and what it means for the Country, especially contamination of the underground water. It is close to the river, which is central to all the life there.”

Desmond Taylor

But there has been disquiet and outright rejection of that agreement ever since, by many Martu including the group behind the Kintyre painting. Martu elder Desmond Taylor, who traces his family heritage through the country around Kintyre, says the risk of uranium contamination of vital water sources is too great to ever allow mining to go ahead.

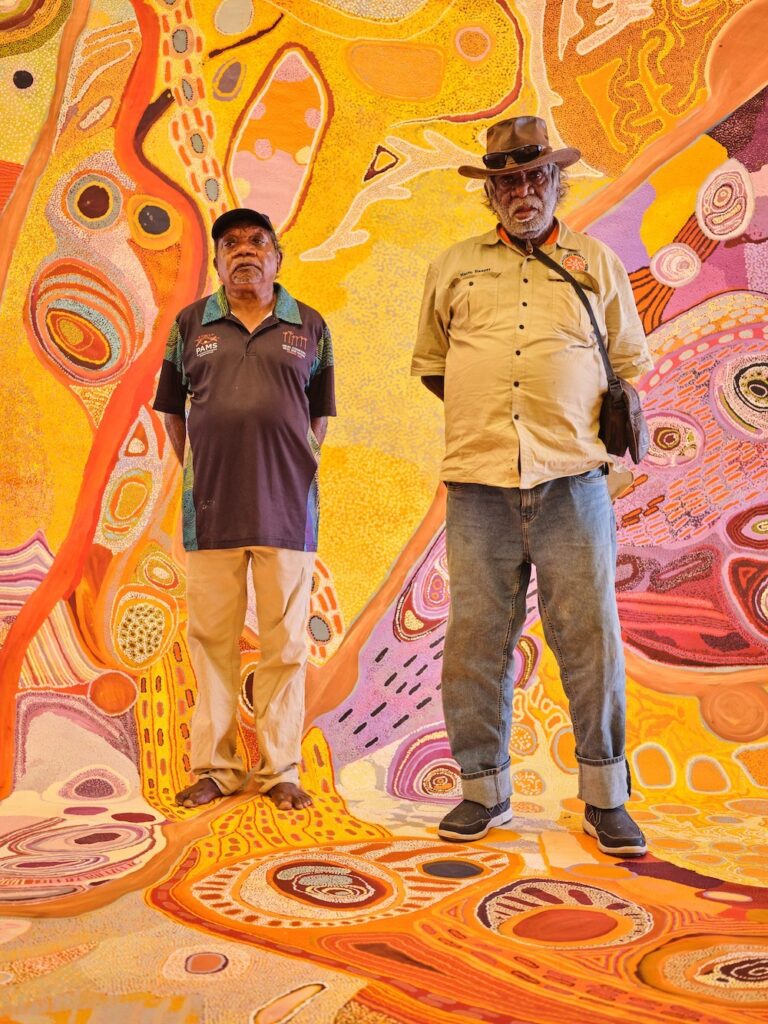

He is one of the key players behind the creation of Kintyre, which has been an epic process in itself, as it took shape during 2020 and 2021 in various locations across Kintyre lands and at Martumili Arts Centre in Newman, where most of the artists involved are represented.

“We are fearful of the uranium and what it means for the Country, especially contamination of the underground water. It is close to the river, which is central to all the life there,” Taylor says.

He dismissed the agreement with WDLAC secured by Cameco in 2012. At the time WDLAC leaders spoke about the need to embrace the development for the income and jobs it would bring their people.

But Taylor says that the complexity of the agreement combined with language barriers meant some of the elders were not fully aware of the implications of the agreement they were signing.

“The majority are against that agreement now. Things have changed,” he says.

WDLAC, now named Jamukurnu Yapalikurnu Aboriginal Corporation, released a statement early this year on behalf of all Martu people, reiterating that they “never agreed to their country being taken away”.

Focal point of major exhibition

Kintyre has been on display as a focal point of the landmark “Tracks We Share” exhibition at the Art Gallery of Western Australia since March. That exhibition closes at the end of August but Kintyre will be front and centre of three days of artists talks and activities at the gallery from this Friday (19 August).

Taylor will be among the Martu artists to tell the story behind Kintyre once again, hoping that the artwork will, in its own quietly spectacular way, sway more opinions in their favour.

He wants the painting to be seen by a much bigger audience and for people across the world to hear the Martu’s plea for their country.

“I hope the National Gallery of Australia might purchase the painting and for our people to get an ongoing benefit from it,” he says.

He is also keen to see the work tour overseas, especially to communities in places such as Canada which have also felt the effects of uranium mining.

“We want to keep sharing our story,” Taylor says. “The elders are happy to share. We hope it can capture the hearts of people when they see it.”

The process of making the painting was about passing on knowledge from elders to the next generation about Country, culture and language, says Taylor. “We talked about maintaining country and protecting it.”

Everything about the Country has been put down on the expanse of canvas as the artists worked in groups on the floor, encapsulating Kintyre’s history and status as a spiritual place, its waterways, claypans, the road – and the uranium deposit.

The result is a work of prodigious scale and power which the artists have presented as a political message, as well as a bold statement about their connection to their traditional country and the need to have it back under their hands.

Projects stalled

Cameco’s two WA uranium ventures – Yeelirrie in the northern Goldfields and Kintyre – both gained political and environmental approvals under WA’s previous Liberal government, but the political and economic numbers have yet to add up for them to proceed beyond the exploration stage.

“We want to create a new story. We are asking Cameco in good faith to hand that land back to the Martu. It’s the only thing we can do; keep talking and telling our story.”

Curtis Taylor

The McGowan Labor Government has a policy of opposing future uranium mines but not overturning the four projects already approved before it came to power in 2017. Cameco’s approval for Kintyre lapsed in 2020 because of its failure to progress the project within five years. As a result, its exploration camp at Kintyre is quiet. But because the company still holds the lease, activists fear a future government could easily reverse this situation and give the project the green light again.

The Conservation Council of WA (CCWA) has been fighting to keep uranium mining out of the State for decades and says the McGowan Government now has a unique opportunity to completely withdraw the expired approval and create lasting protections against future bids to mine uranium at Kintyre. The group strongly supports calls by the Martu people to restore their native title rights over Karlamilyi National Park and for the boundaries to change to re-incorporate Kintyre into the conservation area.

CCWA nuclear free campaigner Mia Pepper says the area was home to endangered species, including the black-flanked rock wallaby and northern quoll.

“The surface water, groundwater and permanent water holes in the Karlamilyi park are connected to the Yantikutji creek at Kintyre – this intricate network of water is incredible and precious and should be permanently protected by withdrawing the approval and incorporating Kintyre into the national park,” she says.

Cameco did not respond to requests for a response to the Martu artists’ Kintyre protest but it has previously said it continues to advance the project “at a pace aligned to market conditions”.

Apart from wanting the Kintyre country returned to the refuge of the national park, Taylor says the Martu are also in discussions with the State Government about giving the Martu a role in the management of the park through the deployment of Martu rangers to help care for the country.

Linking generations

“The younger artists have learnt something from the process, and it has given them hope I think and an understanding that they can be heard, and that they have a role in looking after the country,” says Taylor.

His son, Curtis Taylor, is one of the younger artists involved in the creation of Kintyre who are determined to maintain and strengthen their connection to country.

Curtis, an established multi-discipline artist, helped lead the painting process but says it was the “old people” who directed the composition as they relayed their deep knowledge of their country.

He says the idea for the collaborative painting first took hold in 2016 when a group of Martu staged a week-long 110km walk from the Parnngurr community to the Kintyre exploration area as a way of drawing attention to their struggle. Curtis says it was a great experience for those involved – young and old alike – in reconnecting with country and helping all of them to see it differently.

“It gave us time to see the country and for the younger ones to learn something about all the important places, to talk about it. The idea of painting came out of that.

“We still know that we are a part of that country. We are related to the land, we have a living memory of being there.

“We want to create a new story. We are asking Cameco in good faith to hand that land back to the Martu. It’s the only thing we can do; keep talking and telling our story.

“We hope that the government or the company will listen to us. We’ll keep making a noise until somebody listens.”

Representatives of Martumili Artists will talk about Kintyre at “The Politics of Canvas” session on Saturday 20 August, part of three days of free activities at the Art Gallery of WA to mark the end of the “Tracks We Share” exhibition, which officially closes on 28 August.

Pictured top are ‘Kintyre’ artists Robina Clause (left), Judith Anya Samson, and Corban Clause Williams at Martumili Artists, 2021. Full artist list: Chloe Jadai, Corban Clause Williams, Curtis Taylor, Derrick Butt, Desmond Taylor, Ignatius Hamzah Taylor, Jenny Butt, Judith Anya Samson, Kiarah Jadai, Kumpaya Girgirba, Maisie Nungarrayi Ward, Marilyn Bullen, Mayika Chapman, Muuki Taylor, Nola Ngalangka Taylor, Ngamaru Bidu, Robina Clause, Nikeal (Noni) Taylor, Nuria Jadai, Tamisha Williams, Wokka Taylor (dec.), Yvonne Mandijalu, Christine Thomas.

Photo: Claire Martin.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.