Generous and powerful, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s Perth Festival exhibition explores the role of the night sky in First Nations culture, as a bridge between this world and other realms, writes Ilona McGuire.

A leap of faith into the abyss

29 March 2023

- Reading time • 7 minutesVisual Art

More like this

- A walk with Tina Stefanou

- A blaze of glorious people

- Diving into the gothic world of Erin Coates

Black Sky, various artists

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

Bringing the blackness of the night sky to ground level, Black Sky provides an opportunity for viewers to contemplate its silent intensity as the boundless and timeless keeper of First Nations knowledge.

Complementing Perth Festival’s theme Djinda (stars), Black Sky curators Jessyca Hutchens and Michael Bonner, with Lee Kinsella and Joseph Williams, have gathered a sparkling line-up of artists: Julie Dowling, Gobawarrah-Yinhawangka Traditional Owners and Michael Bonner, Tracey Moffatt, Tennant Creek Brio, Roy Wiggan, and Joseph Williams Jungarayi, Jimmy Frank Japarula and Lévi McLean.

For us – First Nations People – the night sky holds the stories, the ways of knowing and our sense of direction, bridging realms, even the metaphysical. The works contained within Black Sky speak to those connections, that gateway through which the First People access knowledge and understanding far beyond this contemporary world.

Initially I’m dazed by the light reflecting off Badimia artist Julie Dowling’s oil paintings. I move a little to the right and black faces emerge from even blacker backgrounds. Floating in the void of the canvas, their big eyes gaze over me. It’s as though they have been removed from their contexts elsewhere and placed here for myself and others to simply observe.

I turn around to face a collection of Dowling’s self-portraits at various stages of life and find myself mirroring her sombre expressions. She is watching us as we are watching her within those rectangles. In her own words, “These works are statements of identity, place and the fight for expression as Badimia.”

Over to the right are two large portraits, one of which is of an Aboriginal woman in a field, regal and slender. I see myself in her, same build and similar features, but she is living in a place that I only dream of.

I slip around the corner, and hear an old nanna singing from inside a dark room, though I don’t recognise the language. This is the film work of Gobawarrah-Yinhawangka Traditional Owners and Jingili/Yanyuwa filmmaker Michael Bonner.

I wander inside and instantly my field of vision is immersed by 180-degree views. Landscapes, bird’s-eye views and sky-high drone shots pan across Pilbara country showcasing the beauty of the waterways, desert, sunsets and timelapsed nightsky. Meanwhile, the Gobawarrah-Yinhawangka Traditional Owners/Custodians yarn, sing and speak about the importance of their stories that hold the knowledge of the land I am looking at.

Across the hall, a large draped and roughly cut cloth hangs over half of the entryway to a different space, occupied by the installation Fortuna, by artist collective Tennant Creek Brio. I hear men singing their songs in language, again in a tongue that isn’t mine. Beyond the curtain opens another hall, glittering with scattered metallic found objects, grungy and rusted, overlaid in detailed linework. There are dripping paintings on canvas, boards and cracked TV screens too.

At the centre of this space are two wing-ed pokie-machines. Reminiscent of a cyclops, I snicker until a deep sense of melancholy sets in. I realise that this is a dystopia, a fever-dream, but one that is a reality for so many of our Mob.

Named after the Roman Goddess of fortune, the installation’s mutated pokies are designed to capture “a desire to get free of imposed limitations, to take off, while remaining grounded”, an emotion experienced by many First Nations people. Like nightclubs next to ancient ceremony grounds, this dystopia conjures all that we endure amongst these clashing worlds; to hold on to our culture, to recover knowledge and language, to fight for our land, to support our loved ones, to contribute to our community, to overcome the challenges of everyday life whilst walking in many worlds.

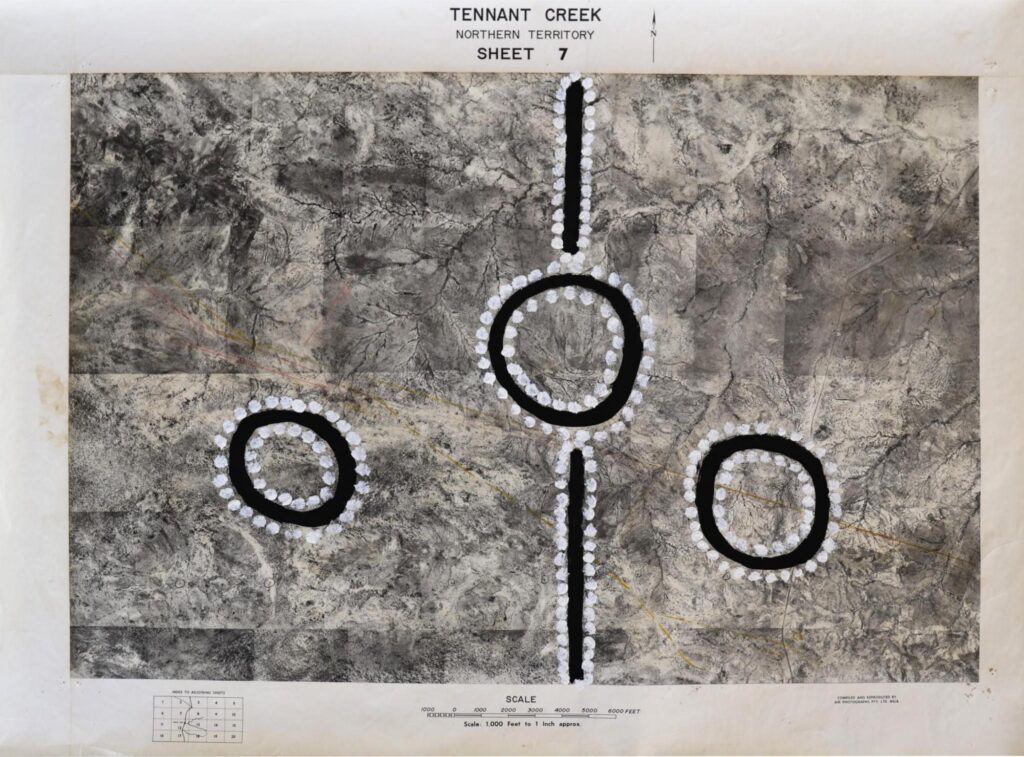

There’s a golden inscription on the wall by the entrance of a neighbouring space. Written in ochre, it looks like gold, different types of currencies that share the same name in Warumungu, the language of artist Joseph Williams Jungarayi. Inside, the back wall is lined with a projection film collaged with mining maps, reflected on the surrounding walls. Each map has been used as a canvas to overlay the artist’s symbols of their country and culture.

As I make it to the back of the room I am shaken by the sound of an explosion coming from the film behind me. I turn around to see a mushroom cloud rising from sacred country being absolutely annihilated. I am deeply shaken. I place my hand on my chest and take a deep breath.

Black Sky is a generous and powerful contribution that offers insight to the complexities of diverse Indigenous perspectives. Like many of Perth Festival’s exhibitions, Black Sky expresses the never-ending vulnerability and open-heartedness of Aboriginal creatives, storytellers, knowledge-holders and the like.

First Nations People are constantly sharing, pouring and contributing in ways that need to be actively heard through response and action. Black Sky reaches out to be heard loud and clear, a leap of faith into the abyss.

Black Sky continues at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery until 22 April 2023.

Pictured: Gobawarrah-Yinhawangka Traditional Owners and Michael Bonner, Gobawarrah-Yinhawangka ‘Horizon Line‘, 2023 acrylic on wall, installation view in Black Sky, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, 2023. Photo: Rebecca Mansell

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.